In Japanese, the numbers 4 and 9 are considered unlucky: When pronounced shi, the number four is a homophone for death (死); when pronounced ku, the number nine is a homophone for suffering (苦). See also tetraphobia. Although this is a holdover from the Western tradition, the number 13 is sometimes considered unlucky. Numbers 7 and sometimes 8 are considered lucky in Japan, on the other hand.

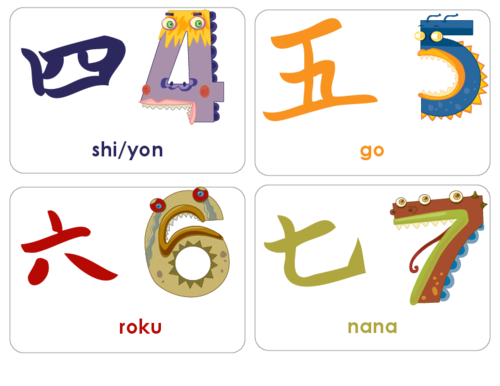

Except for 4 and 7, which are called yon and nana in modern Japanese, cardinal numbers are given the ‘on readings.’ Month names, day-of-month names, and fixed phrases all use alternate readings. For example, the decimal fraction 4.79 is always read as yon-ten nana kyū, despite the fact that April, July, and September are referred to as shi-gatsu (4th month), shichi-gatsu (7th month), and ku-gatsu (9th month) respectively. When shouting out headcounts, the ‘on readings’ are also used (e.g. ichi-ni-san-shi). These elements are combined to form intermediate numbers.

Tens from 20 to 90 are denoted by “(digit)-jū,” as in (ni-jū) to 九十 (kyū-jū).

Hundreds, ranging from 200 to 900, are “(digit)-hyaku.”

“(digit)-sen” thousands range from 2000 to 9000.

There are some phonetic changes to larger numbers that involve voicing or gemination of certain consonants, as is common in Japanese (i.e. rendaku): for example, roku “six” and hyaku “hundred” yield roppyaku “six hundred.”

This also holds true for multiples of ten. Change the -jū to -jutchō or -jukkei at the end. This also holds true for multiples of 100. Change the -ku to -kkei at the end.

Elements are combined from largest to smallest in large numbers, and zeros are implied.

Other than the basic cardinals and ordinals, Japanese has a variety of numerals.

Elements are combined from largest to smallest in large numbers, and zeros are implied.

Other than the basic cardinals and ordinals, the Japanese has a variety of numerals.

A cardinal number, a counter word, and the suffix -zutsu (ずつ), as in hitori-zutsu (一人ずつ, one person at a time, one person each), are used to create distributive numbers on a regular basis.